For me, one of the wonderful aspects of listening to a song or album, is to imagine how the artist visualized or intended that piece of work to be. From imagination to reality, there is a long road.

The artist undergoes a thorough process of composing, producing, mixing and mastering, in order to reach the final version of a tune that everyone will listen. Thus, it is a long process which requires much mental, physical and financial effort. An effort that will hopefully stand the test of time.

And last long after when the artist is gone.

But in recent years we have witnessed an important game changer: The development of AI editing tools and the possibility for anyone to change an existing piece of work. This game-changing scenario has triggered numerous relevant discussions for the industry and artists. For example:

How should artists protect their work from artificial intelligence editing tools? Should they actually or allow for free co-creation from fans? Furthermore, how should artists protect the integrity of their work long after they are gone?

Take the Moises app for example. Moises is an app which allows anyone to upload any song and change the pitch, tone and even exclude instruments from the track. The idea is to allow users to feel part of a band and play along. From one perspective, it is wonderful. It allows amateur and professional musicians to co-create with their favorite artist, practice their instrument or experience existing songs on a different way.

So from a co-creative perspective, it is wonderful. No question.

However, from another perspective, it allows anyone to modify an existing piece of work that was created with a purpose and intention by the artist. Is this ok? Well, complex.

Take for example elaborate tracks such as “A Day in the Life” by the Beatles, “Bohemian Rhapsody”, by Queen, “God Only Knows”, by the Beach Boys and more. These songs contain multiple instruments, orchestral arrangements and are famous worldwide.

And exactly due to the fact that they are multifaceted and complex, they allow for multiple editing and new versions. After all, by simply removing one instrument one can produce a completely new version of a song. Imagine by removing or adding many others.

So with new AI editing tools available, such as Moises, it is not surprising to find many “new versions” of songs, created with the support of artificial creativity tools. Importantly, without the awareness of artists.

Example: “Tuna in the Brine” (Silverchair)

Silverchair is the most successful Australian rock band of all times. They became famous in 1994 with the release of the single “Tomorrow”. It took them quickly to global fame and marked the start of an extremely successful international career.

In 2002, already established as artists, they released their fourth studio album titled “Diorama”. It is, in my view, extraordinary and their most elaborate record. Songs are long, complex and have magnificent orchestral arrangements from the legendary Van Dyke Parks along the ballads and hard rock track.

One of the best tracks of the record is named “Tuna in the Brine”. The song lasts 5 minutes and 41 seconds, and takes the listeners through many different moments. It is complex, non-repetitive and has no chorus. It is a truly a journey. And well, surprise, surprise… One can find online many “new” versions of this track. The version shown below displays the song with one important feature: the acoustic guitar track has been removed.

The result? A completely new version, which emphasizes even more the orchestral arrangement. The problem? The band never intended to have this version. The one idealized by them is the one found on the album. What is, maybe, even worse? This new version sounds great.

Is Open Co-Creation with AI the Future?

It is extremely difficult to regulate and control independent co-creation of existing artistic works, such as music, due to the growing accessibility and development of AI editing tools. Thus, open co-creation powered by AI is, without a doubt, here to stay.

So how to deal with it?

Well, from one perspective, it can represent a new form of engagement between artists and fans and help promote tracks and musicians. Furthermore, many artists will for sure be open to the idea of having their work modified or co-created by others. After all, many will perceive it as a form of artistic expression as well. Especially when many more technologies, such as Moises, are made available.

But what if the artist does not agree with the idea? What if one believes that his or her work should only be perceived the way they envisioned and published?

Well… Here is the tricky part. As i mentioned, it will be extremely difficult to regulate and control such actions. Thus, it is not difficult to imagine artists frustrated for seeing their work being modified without their consent. And many law suits.

And what will happen when future generations can no longer, or simply will not know, what is the original version idealized by an artist and what is a modified piece with AI? Complicated, very complicated…

The complexity of this scenario raises the need for a body of applied research and legislated efforts. Or perhaps, the need for a paradigm shift as to how we envision one’s work legacy and the way it is viewed and protected for future generations.

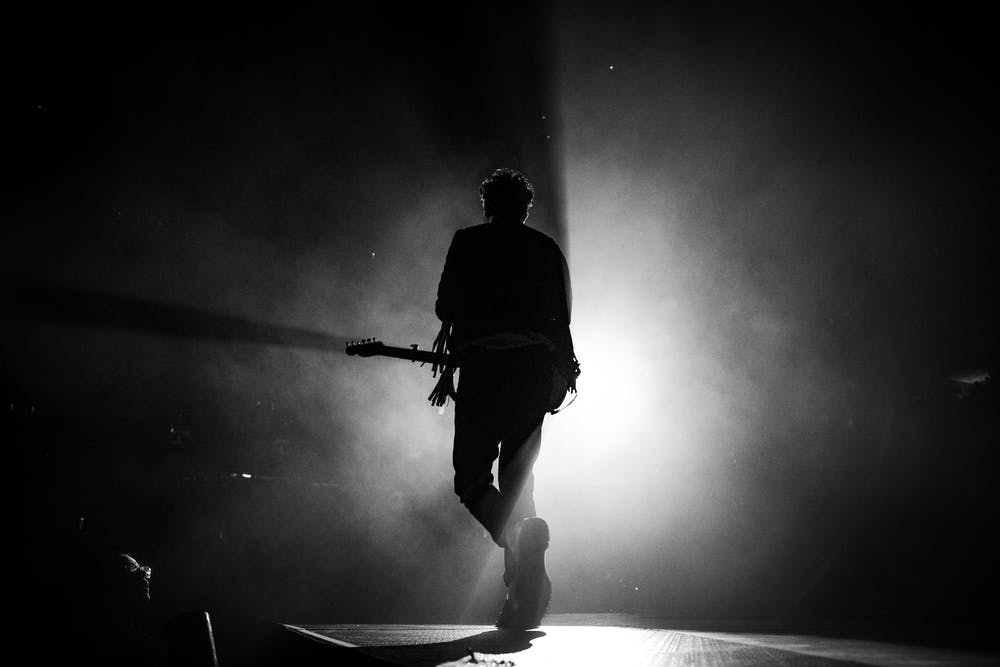

Closing the Curtains

Just to make clear: I do not oppose AI editing tools. Personally, I believe they enable new forms of creativity and open new streams of co-creation. And I certainly have nothing against Moises, which I actually admire, have downloaded and am curious to see how will evolve.

Nevertheless, the discussion on artificial creativity, rights and legacy needs to move further. We need to understand all aspects of this matter and certainly investigate how musicians feel about it. Probably an important topic for the next Live AM: Artist Monitor.